What’s in a Narrative? Techniques for Developing Engaging Briefs to Maintain Shared Understanding of the Enemy

Introduction

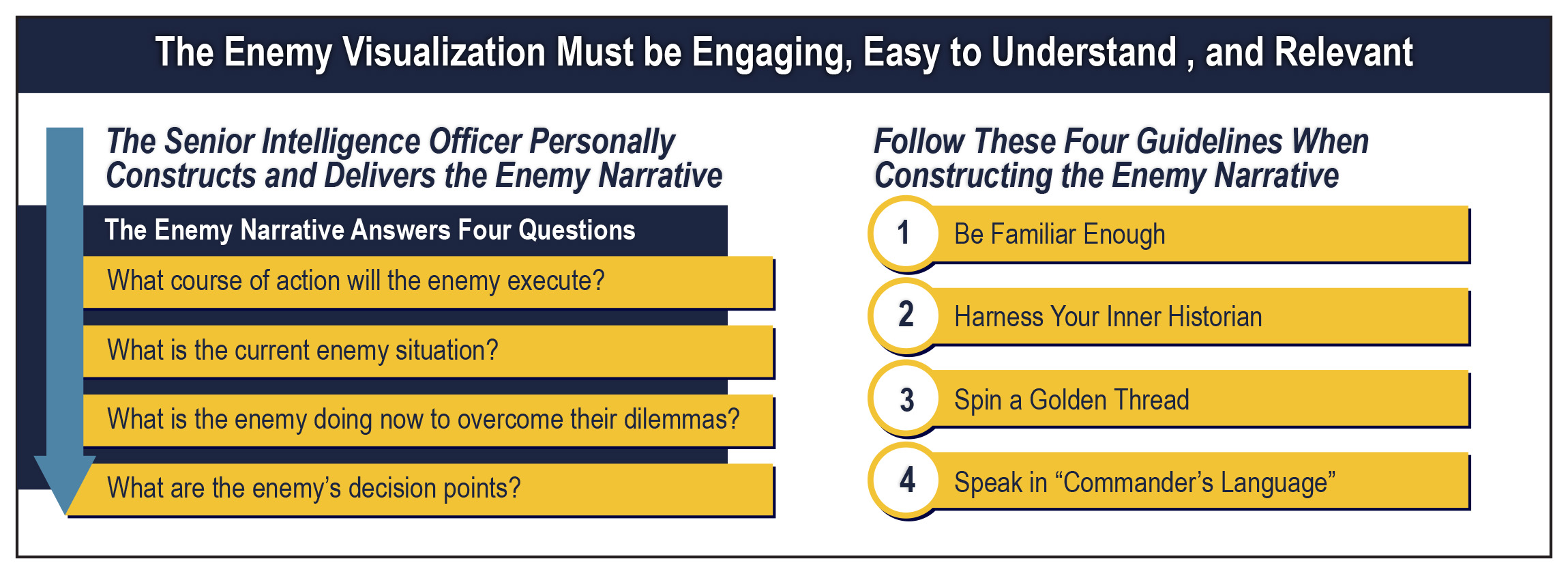

Senior intelligence officers and their intelligence cells owe their commanders and units an engaging, easy-to-understand, and relevant visualization of the enemy. However, even perfect enemy narratives are meaningless if they do not lead to a shared understanding of the threat across the formation.

Unfortunately, large-scale combat operations present three key problems that significantly complicate the production and shared visualization of a quality enemy narrative. The first problem is the scope and dynamism of large-scale combat operations, which challenge even the best intelligence cells to make sense of the operating environment. Compounding this issue is the second problem; namely, how to maintain a common enemy narrative when the senior intelligence officer is often geographically separated from the analysis and control element (ACE), brigades increasingly do not have a brigade intelligence support element, and the continuous upper tactical infrastructure’s connectivity that once supported unlimited voice and video conferencing can no longer be assured. The third problem also concerns communication; however, it is not related to intelligence architecture, nor does it result from tactical dispersion. The intelligence cell must find a way to reduce the inherent complexity of large-scale combat operations into a succinct brief that is immediately understandable and useful to time-constrained, exhausted commanders. These three problems place a heavy premium on intelligence assessments that deliver the right intelligence at the right time in easily digestible formats that speak to the commander and staff.1

This article describes the technique used by the 1st Infantry Division in large-scale combat operations training environments to keep the enemy narrative current, widely understood across the formation, and relevant to the commander. This technique is not described in doctrine, but its recommendations touch upon the fundamental role of the senior intelligence officer: to keep everyone—commanders, staff, subordinate S-2s, and their intelligence sections—engaged and to foster a shared understanding of the enemy narrative in high-paced, dynamic environments. If implemented, this technique will pay significant dividends for your unit.

This article is presented in three parts:

- Part I demonstrates why the senior intelligence officer is central to constructing an engaging enemy narrative in large-scale combat operations.

- Part II identifies the four questions an effective narrative addresses, along with four guidelines to ensure the narrative is maximally engaging for the commander and staff.

- Part III describes the 1st Infantry Division’s technique to construct its enemy narrative. The 1st Infantry Division G-2 developed this technique during Warfighter Exercise 25-02 and later refined it during its division-in-the-dirt rotation. The method ensured the unit maintained a common understanding of the enemy while operating across the battlefield in tactically dispersed nodes.

PART I: The Senior Intelligence Officer as Narrator

During large-scale combat operations, senior intelligence officers must personally draft the outline of the enemy narrative and often brief it during key battle rhythm events. Retired Lieutenant Colonel Terry R. Ferrell, a mentor from the Mission Command Training Program, noted that a unit’s battle rhythm does not always coincide with the battle’s rhythm and, therefore, units must adapt their meetings and boards to the dictates of the operational environment.

For some senior intelligence officers, this central recommendation will come as no surprise; it’s how they do business now. However, please read on for ideas on the essential elements of an engaging enemy narrative in Part II, along with how to organize and direct your intelligence cell to fill in the supporting details (thereby allowing the senior intelligence officer to get some rest!) in Part III. For other senior intelligence officers who take a more managerial approach to running their intelligence sections, the technique described here might push them out of their comfort zone. That’s okay. The demands of large-scale combat operations require change, but the benefits of this technique far outweigh any discomfort. Even if you’re not a senior intelligence officer, this article will provide you with valuable knowledge to better support your cell’s senior leadership and, as a result, the commander, influencing decision making and achieving the desired results.

Why is it necessary for the senior intelligence officer to personally construct the narrative outline and brief, as opposed to, say, a senior member of the ACE? With its more robust staffing and network connectivity, the intelligence cell excels at describing the enemy situation. Where they may fall short, however, is in their understanding of what friendly forces are doing or will do. In environments requiring tactical dispersion, only the senior intelligence officer has access to situational intelligence from over-the-horizon cells and to emerging developments near the forward edge of battle that will shape future actions. While the forward staff can relay developments to the intelligence cell as conditions permit, there is no substitute for the understanding that develops during the face-to-face dialogue between the senior intelligence officer and senior leaders at or near the area of danger.2

A unit can form a complete enemy narrative only by understanding what the threat is doing now and what the friendly force will do against them in the future. A complete narrative predicts the enemy’s next likely moves based upon the friendly forces’ intended actions by retrospectively examining how the threat and friendly forces arrived at their current situation.3 In the language of wargaming, the intelligence cell has the action but not the current or developing friendly reaction that directly impacts what the enemy will do in the future.

That’s where the senior intelligence officer comes in. The senior intelligence officer’s unique access to the commander and senior staff provides the insights needed to understand what friendly forces are doing and intend to do against the enemy. A compelling enemy narrative conveys the threat’s counteraction—how the enemy could achieve its end state given its current disposition and actions in light of the expected friendly response. In large-scale combat operations, the senior intelligence officer’s mind is a continuously running wargame simulation, examining, from the enemy’s perspective, what the friendly force will do next, given the battlefield realities and the enemy and friendly commanders’ desired aims.4

For a deeper discussion on the challenges of the future battlefield for the intelligence warfighting function and the unique role of the senior intelligence officer, see the author’s two-part 2024 article, “A Mission Command Meditation.”5

PART II: Developing Effective and Engaging Narratives

So, what’s in an enemy narrative anyway? A compelling narrative answers four key questions and forms an essential component of the intelligence running estimate. However, before discussing the four questions, it will be helpful to review general guidelines for boosting a narrative’s digestibility and engagement.

Guidelines for Constructing the Enemy Narrative. Senior intelligence officers must maximize the limited time and mental energy available to the commander and staff during battle rhythm events or as the battlefield situation dictates. The following guidelines ensure the unit gets the easily digestible, engaging visualization of the enemy they need to make decisions in complex operating environments. (See figure below.) The four guidelines are:

- Be familiar enough.

- Harness your inner historian.

- Spin a golden thread.

- Speak in the “commander’s language.”6

Be familiar enough. The enemy narrative brief should always follow the same general structure, but it need not conform to a precise format—it should be familiar enough. This simple guideline lets the audience digest information more quickly because they know what to expect. Examples of being familiar enough include always starting the brief with the overall assessment or always describing the enemy disposition within the area of interest first, followed by the area of operations using the deep, close, and rear framework. However, briefers should refine the brief based on battlefield developments.7 For example, a possible adjustment might include spending more time than usual on enemy disposition or future action, particularly if the latest information conflicts with previously held assessments. It might also include detailed combat power slant reports on enemy forces for specific objectives, but none for others. Following a general format is helpful, but always brief about what the audience needs to know now. Whatever you do, though, always start with an overall assessment of what course of action (COA) the enemy is taking or about to take.

Harness your inner historian. The second helpful guideline to improve ease of understanding and engagement is to harness the tools historians use. Author John Lewis Gaddis believes:

Historians have the capacity for selectivity, simultaneity, and the shifting of scale: they can select from the cacophony of events what they think is really important; they can be in several times and places at once; and they can zoom in and out between macroscopic and microscopic levels of analysis.8

Like historians weaving a historical narrative in a work, senior intelligence officers must leverage the concepts of selectivity, simultaneity, and the shifting of scale when discussing the enemy narrative. I have argued previously that competent senior intelligence officers are adept curators of information, selecting reports or pieces of essential information with outsized impact on the current understanding of the enemy situation.9 In Gaddis’s terms, by curating information—choosing only information that the commander and staff must know to support effective decision making—the senior intelligence officer demonstrates their capacity for selectivity.

Senior intelligence officers also highlight specific information across the division’s battlefield framework (rear, close, deep areas) and within the area of interest. The selection of necessary information across the battlefield demonstrates a senior intelligence officer’s capacity for simultaneity by nesting enemy actions within the unit’s rear, close, and deep fight in relation to the broader context of the enemy’s higher echelon operational COA.

Finally, senior intelligence officers must be masters of the shifting of scale. In the span of a few briefing points, the senior intelligence officer could, for example, describe the actions of an enemy corps in the area of interest, the task and purpose of an enemy division about to enter the unit’s deep area, and the suspected location of a single vehicle on the high-payoff target list. The senior intelligence officer’s challenge is to leverage Gaddis’s concepts without confusing the audience or muddying the main message, which is where the next guideline comes in.

Spin a golden thread. The third guideline calls for the senior intelligence officer always to weave a golden thread into the intelligence brief. A golden thread brings coherence to your story: “It’s the theme that takes you from beginning to end.”10 A discussion of golden threads starts where the first guideline left off. Senior intelligence officers must always begin the brief with the key analytical judgment (anticipated enemy COA), which serves as the central golden thread around which the senior intelligence officer will organize the remainder of the brief, employing Gaddis’s concepts of selectivity, simultaneity, and the shifting of scale. Here is an example of a central golden thread:

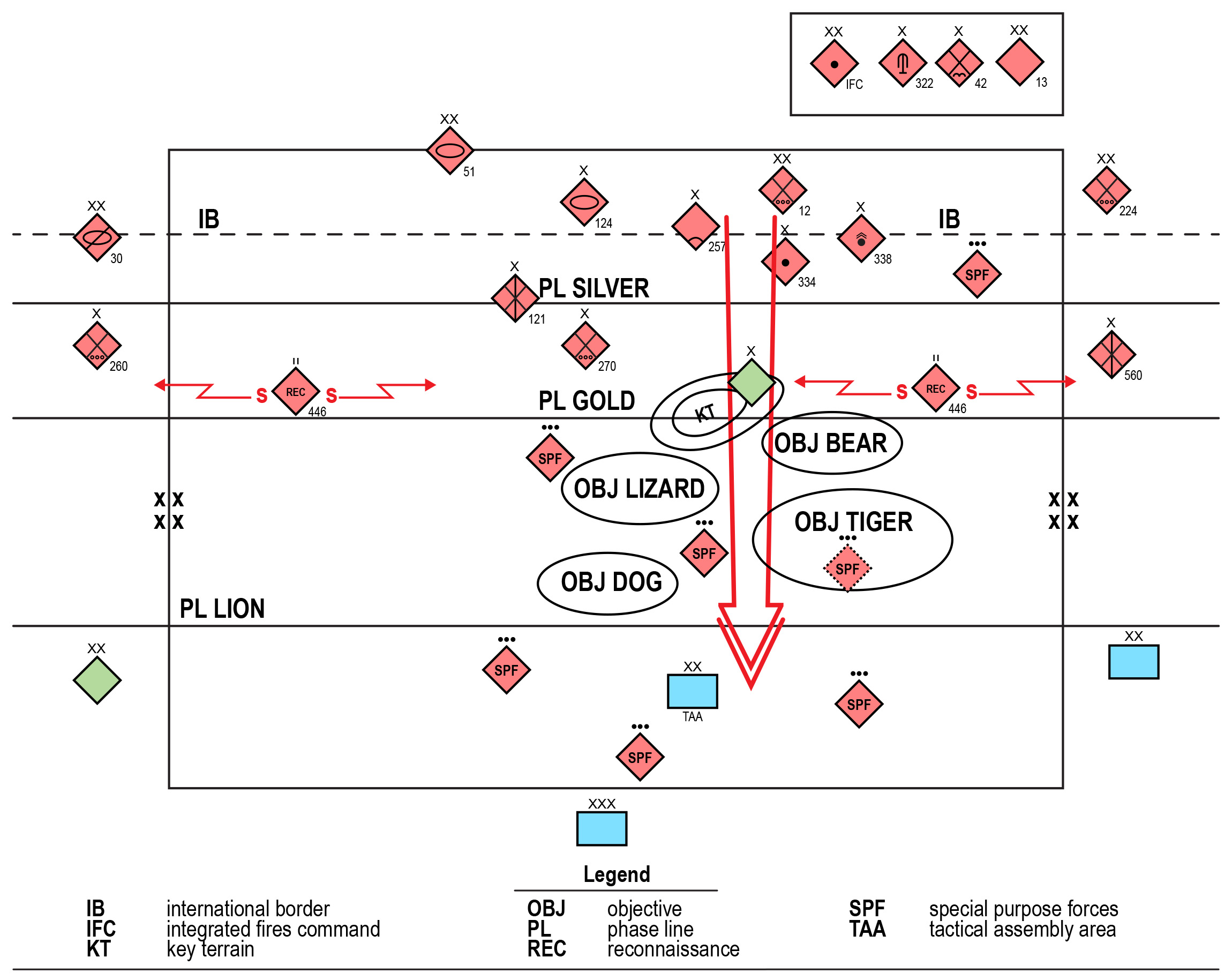

The 11 DTG [division tactical group] will attack to destroy YOUR UNIT no later than 2400 hours to enable the seizure of OBJ [objective] DOG by the 12 DTG.

Figure. Crafting an Engaging Enemy Narrative (Figure by author)

The golden thread—the 11 DTG attack to enable the 12 DTG—should resonate throughout the intelligence update, including the enemy situation and anticipated future actions. It should also connect with what other intelligence personnel discuss in the intelligence estimate’s components, including weather, collection management, and battle damage assessment updates.11

The weather update, for example, should discuss how the conditions will help or hinder the attacker. The collection manager should brief on how assets will detect the axis and the weighting of the 11 DTG attack, and the entrance of the 12 DTG into YOUR UNIT’s deep area. The targeting officer should brief the remaining strength of the critical 11 DTG assets needed to suppress, obscure, secure, reduce, and assault friendly defenders during its predicted breaching operations and the targeting efforts ongoing to reduce those specific forces.

Too often, intelligence briefings lack synchronization or fail to present a more compelling argument for what the enemy is doing or will do next, and what it means for the friendly force. Without a strong golden thread—a persuasive, easily understood central argument—the brief can become a “confusing mess: tangled balls of string floating in murky soup.”12 You can read more about the need for precise intelligence assessments and how to improve them in the author’s 2022 article, “Stating the Obvious: The Three Keys to Better Intelligence Assessments.”13

True success, however, comes when the golden thread introduced during the intelligence update carries into the operational update, providing a seamless narrative of how the friendly force will mitigate risks or seize opportunities presented by the threat commander.

Speak in the commander’s language. Finally, members of every military community, including the intelligence community, speak to each other using jargon familiar to all community members (for example, any discussion, ever, on the Distributed Common Ground System-Army). When briefing the enemy narrative, however, it’s the senior intelligence officer’s job to speak primarily in the language of commanders. This is simply because the commander does not have the time or energy to translate the senior intelligence officer’s brief into the information needed to make sense of the environment or to make decisions.14 It’s also the briefer’s job to engage their audience, and how better to do this than to use the language already esteemed by commanders?

What language do commanders use when speaking to one another? Commanders rightfully focus on the decisions they must make and on transitions. Therefore, it is no surprise that commanders’ narratives center on “decisions (what and when), risks, opportunities, options, transition points, condition setting, and resource shortfalls (to request from a higher headquarters).”15 Senior intelligence officers should make maximal use of these concepts and language throughout their updates, especially when describing the enemy narrative from the enemy commander’s perspective and discussing the “so what” of their assessments from the friendly commander’s perspective. By using the language of commanders, senior intelligence officers can provide intelligence that is directly relevant to the unit’s decision-making process.

Let’s return to the golden thread assessment to illustrate these points:

The 11 DTG will attack to destroy YOUR UNIT no later than 2400 hours to enable the seizure of OBJ DOG by the 12 DTG.

To leverage the language of commanders while briefing this enemy narrative, the senior intelligence officer could discuss enemy decisions related to the 11 DTG attack—say, a weighting of its main effort along one avenue of approach or another. The senior intelligence officer could examine the conditions the enemy would need to set for this decision (for example, neutralizing a friendly screen), thus highlighting the intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance options available to detect the enemy COA, or the intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance resources YOUR UNIT needs to request from your higher headquarters. The senior intelligence officer could then discuss the risks of the 12 DTG attacking through YOUR UNIT’s area of operations to seize OBJ DOG while highlighting friendly opportunities to destroy critical 12 DTG equipment or formations at canalizing terrain with attack aviation. Finally, the senior intelligence officer could conclude by predicting the enemy failure option, describing how the enemy might transition to a defense when its attack to defeat YOUR UNIT fails.

The Four Questions of the Enemy Narrative. So, now that we have reviewed the prerequisite guidelines, let’s return to the four questions of the enemy narrative. The four questions are:

- What COA will the enemy execute?

- What is the current enemy situation?

- What is the enemy doing now, given the current or anticipated dilemmas it faces?

- What are the enemy’s decision points?

What COA will the enemy execute? Every battle update brief and commander’s update brief must begin the same way, with the senior intelligence officer answering the question: What COA will the enemy execute? The answer—the golden thread of the brief—might discuss the COA the enemy is executing now or an upcoming one. Leveraging Gaddis’s concepts of shifting of scale and simultaneity, the senior intelligence officer’s answer could also include the operational-level COA of the enemy headquarters one to two echelons higher, especially if this COA had a substantial likelihood of influencing the unit’s operations or, just as importantly, if a divergence between the division’s and the higher headquarters’ read of the enemy was emerging. Returning to the discussion tied to the familiar enough guideline and Gaddis’s concept of selectivity, the senior intelligence officer presents only the COAs the commander and staff need to know. Alternatively, speaking in the language of commanders, the senior intelligence officer could brief the conditions the enemy must meet before executing a particular COA, the opportunities and risks of implementing it, and how the enemy will transition to a failure option if they do not achieve the desired end state.16

What is the current enemy situation? With the golden thread now identified, the next question for the senior intelligence officer to answer is: What is the current enemy situation? The answer to this question provides the commander and staff with a description of the enemy’s composition, disposition, strength, and, most notably, how we got here. In large-scale combat operations, the battlefield will be awash with information, sometimes making it difficult to present the enemy situation succinctly. To tackle this problem, the senior intelligence officer should describe the enemy disposition using the same structure during every brief (the “familiar enough” guideline). A practical framework for explaining the enemy situation is to start with the enemy formations furthest from your unit and work your way into the close area, or vice versa. With a familiar framework in place, the senior intelligence officer can once again leverage the historian’s tools to keep the narrative flowing and use the language of commanders to keep it relevant.

For example, the senior intelligence officer could begin this portion of their narrative by identifying the combat power of a unit in the area of interest that is most likely to influence the friendly force, expressed as a percentage. The senior intelligence officer could then list the combat slant for formations in their unit’s deep area, plus an even more detailed slant, task, and purpose, and the assessed decision points by objective in the unit’s close area (a technique recommended by cadre at the National Training Center). All this occurs in a few minutes thanks to careful use of simultaneity, shifting of scale, and selectivity. Throughout the brief, the senior intelligence officer notes the opportunities and risks presented by the enemy situation to the commander and staff for keeping the friendly force engaged.

What is the enemy doing now, given the current or anticipated dilemmas it faces? In about 3 to 5 minutes, the senior intelligence officer has identified the central argument (selected enemy COA) and described how the enemy has positioned itself (enemy situation) to accomplish its mission. The senior intelligence officer must now explain what the enemy will do next to overcome the friendly force situation and actions, along with the ever-present challenges of limited time, rugged terrain, finite resources, and many other considerations.17 These factors—the enemy’s dilemmas—are essential to a compelling narrative.

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines a dilemma as “a problem involving a difficult choice.”18 Dilemmas are a constant feature of large-scale combat operations for enemy and friendly forces, even when things are going well. There are never enough resources, time, or a pliant opposing force in war. Few decisions in war are easy, and most require less-than-ideal tradeoffs that the commander must grudgingly accept to accomplish the mission.19

Given that dilemmas are central to military operations, the senior intelligence officer must identify the enemy’s dilemmas and determine how to overcome them (thereby creating new dilemmas for the friendly force). Describing the enemy’s dilemma is, in fact, the “heart” of the intelligence brief, and by exploring it, the senior intelligence officer helps “distill” a complex situation—what an enemy formation will do given friendly forces and their actions—into its “clearest meaning.”20

The senior intelligence officer starts by retrospectively reviewing the enemy’s progress along their assessed line of operations to explain how the enemy reached this point. Next, they describe the objectives (condition-setting) the enemy must fulfill over the next 12 to 24 hours, either to achieve an end state or to progress toward it. The senior intelligence officer then discusses what is preventing the enemy from achieving their objectives and what they will do to overcome the obstacles, using the language of commanders, such as opportunity and risk.21

Discussing the enemy’s dilemmas and their actions to overcome obstacles is one of the most straightforward yet powerful tools a senior intelligence officer can use when briefing a narrative. This addition to the narrative compels the friendly command and staff to view the commander empathetically and create effective countermeasures and counteractions. Use it!

To illustrate these points, let’s go back to the golden thread assessment. The senior intelligence officer assesses:

The 11 DTG will attack to destroy YOUR UNIT no later than 2400 hours to enable the seizure of OBJ DOG by the 12 DTG.

When discussing what the enemy is doing now, given the current or anticipated dilemmas they face, the senior intelligence officer may begin by stating how the 11 DTG got to its current position retrospectively, listing the objectives along a geographic line of operations they previously seized and noting advantageous terrain they are likely to seize next to ensure a successful attack. The senior intelligence officer could then describe the enemy dilemma, noting, for example, that the enemy must destroy YOUR UNIT by 2400 hours without the benefit of overwhelming combat power. Next, the senior intelligence officer could describe how the enemy corps (shifting of scale) could use enablers, such as its Multiple Launch Rocket System or attack aviation assets, to create a more favorable situation for the 11 DTG commanders. Notably, the senior intelligence officer includes intelligence (selectivity again) that supports this assessment or recommends options for changing the collection plan to uncover indicators that the enemy is or is not mitigating its unfavorable combat power ratios in this way. In response, the friendly commander approves the collection tasks (perhaps as a new priority intelligence requirement) and offers other guidance to mitigate or, preferably, exploit the threat’s latest actions (risks and opportunities).

What are the enemy’s decision points? At this point, the senior intelligence officer has conveyed the assessed enemy COA, the enemy’s current situation, and the problems the enemy must solve to continue its line of operations. The senior intelligence officer now concludes the brief by describing the decision points available to the threat commander and, as necessary (selectivity), the location, time window, and conditions for each decision. The base product for this portion of the brief is the event template.

Senior intelligence officers also use estimative language when describing how likely a threat commander is to make or not make a particular decision and how confident they are in that assessment. In the language of storytelling, low likelihood decision points are like plot twists, feasible actions that the enemy could take but would be surprising if executed.22 Conversely, decision points with a higher assessed probability of occurrence are more like subplots that add color to the storyline (the assessed enemy COA) but don’t change its overall essential features.23

Either way, all decision points relate to the golden thread woven throughout the brief and summarize key points in the commander’s language. This portion of the brief also provides another opportunity to confirm that the collection is aligned to detect the enemy decision points and ensure that the friendly force plan can mitigate or exploit the decisions the enemy makes.

To illustrate these points using the 11 DTG attack on YOUR UNIT, the senior intelligence officer identifies two decision points. One decision point concerns the avenue of approach the 11 DTG will use to weight its main effort. It could read as follows: Decision Point 1: Weight the 11 DTG main effort along Avenue of Approach 1 or 2. The other decision point is a plot twist, the 11 DTG commander‘s decision not to conduct an attack but to transition to defensive operations. The senior intelligence officer discusses the likelihood of either occurring and the relevant points regarding time, location, and conditions.

PART III: Maintaining Shared Understanding

The final part of this article describes the technique the 1st Infantry Division G-2 used to maintain shared understanding while tactically dispersed.

Organizing the Intelligence Cell. The 1st Infantry Division took a leadership-forward approach to organizing its intelligence cell for large-scale combat operations. While the purpose of this article is not to discuss the most effective ways to task-organize the intelligence cell during large-scale combat operations, it may be useful to understand the general location of the 1st Infantry Division’s military intelligence leaders on the battlefield. This information will illuminate how this organization influenced the construction of a definitive narrative twice daily. The 1st Infantry Division organized two primary mission command nodes during its division-in-the-dirt NTC 25-03 rotation in January 2025. The main command post had the following key personnel:

- G-2.

- Collection manager.

- Targeting officer.

- Current operations day and night officers in charge.

- G-2 planner.

- Chief fusion officer.

- ACE production manager.

The primary benefit of having intelligence leaders forward in the main command post was the face-to-face dialogue that was possible between these leaders, the commander and staff, and the G-2 and primary subordinates.

The rest of the Division ACE, along with the ACE Chief, was co-located with the rear command post. Stationing the ACE rearward on the battlefield, with the rear command post, ensured connectivity due to fewer required jumps. This allowed the ACE to provide near-uninterrupted support to targeting and to develop detailed analytic products.

Drafting the Narrative. Separating the ACE from the main command post led to a familiar problem: maintaining a shared enemy narrative in an environment that requires tactical dispersion. The 1st Infantry Division senior intelligence officer briefed a formal enemy narrative twice daily, as battlefield conditions permitted, first during the battle update brief in the early morning and again during the commander’s update brief in the evening. Both briefs provided similar information, answering the four questions of an enemy narrative. However, the battle update brief was often a more extensive update, covering all elements of the intelligence running estimate, including the weather, collection plan, significant activity, targeting, updates to battle damage assessments, and an overview of the event template. The commander’s update brief focused solely on the enemy narrative and collection plan. The respective cell leadership, such as the staff weather officer or targeting officer, briefed the other components of the running estimate outside the narrative.

The 1st Infantry Division senior intelligence officer drafted the narrative for the battle update brief immediately following the commander’s update brief, leveraging the understanding that emerged during the commander’s dialogue to craft initial responses to each of the four questions. Once drafted, the senior intelligence officer at the main command post digitally sent the narrative to the ACE in the late evening and, on a good night, got some rest. The ACE night shift then completed the draft, filling in critical details and updates as the evening progressed, confirming, denying, or providing wholesale new components to the narrative as the battle continued throughout the night.

Early the following morning, the senior intelligence officer returned and reviewed the newly completed narrative. Soon thereafter, the senior intelligence officer and G-2/ACE leadership discussed and rehearsed the narrative, making changes or adjustments as necessary. Often, this dialogue spurred new insights that the senior intelligence officer incorporated into the narrative. This dialogue also allowed the other intelligence briefers to include the golden thread in their portions of the overall battle update brief. Before briefing the commander, the ACE distributed the narrative script throughout the unit via intelligence channels to provide the basis for subordinate unit S-2 briefs to their own commanders, ensuring a shared understanding of the threat.

Later in the morning, the senior intelligence officer briefed the commander and received guidance. The senior intelligence officer also noted changes in the friendly situation and plan that could impact future enemy activity during the other staff updates. That evening, immediately following the battle update brief, the narrative drafting process repeated with information updated as appropriate. Once again, the senior intelligence officer drafted new or updated answers to the four questions, using information gleaned from the battle update brief, battle rhythm events, intelligence reports, and battlefield updates throughout the morning. Once complete, the senior intelligence officer sent the draft to the ACE for fine-tuning and completion. In the early evening, the senior intelligence officer and ACE met again to review the completed narrative draft in preparation for the evening commander’s update brief.

The preceding vignette is an example of a completed, “brief ready” script that a division senior intelligence officer might brief before an anticipated enemy invasion or command post exercise starts. The script is modeled after those developed by the 1st Infantry Division during its Warfighter exercise and division-in-the-dirt rotation. Generally, the narrative should take about 5 to 7 minutes to deliver, but this example is longer than a typical script to include more examples of the four guidelines. While there are no fixed rules regarding script length, the bottom line is to say no more than necessary and certainly not less. The blue words in brackets highlight both answers to the four questions and callbacks to the four guidelines. Importantly, though the word “script” is used here, the senior intelligence officer should use it only as an outline in face-to-face briefings, never reading it verbatim to the commander unless providing a distributed update via electronic communication.

The 1st Infantry Division found this method to be the most efficient and effective way to maintain shared understanding. It leveraged the senior intelligence officer’s access to the senior staff, commander, and information at the edge of the battle to develop a strong framework response to each of the four questions. Armed with that framework and the direction it provided, the ACE found it easy to complete the narrative, enabling it to expend more energy on other activities such as support to targeting, analytical deep dives, and support to information collection without having to “guess” what was in the mind of the senior intelligence officer or commander.

Conclusion

It is the senior intelligence officer’s job to ensure everyone has the same understanding of the enemy. This is a formidable task given the inherent complexity, the physical and mental tolls, and the requirement for tactical dispersion of large-scale combat operations. The senior intelligence officer must draft engaging, easily understandable narratives in this environment, often for exhausted and combat-stressed leaders. Intelligence cells accomplish this challenging task by creating briefs that provide clear responses to the COA the enemy commander selected, the current enemy situation, projected enemy activity given their assessed dilemmas, and their decision points. The senior intelligence officer makes these responses more compelling and digestible when their brief uses a familiar structure and leads with a central argument that threads throughout. The enemy narrative gains greater appeal when the senior intelligence officer speaks in the language of commanders and skillfully communicates using the historian’s tools of selectivity, simultaneity, and shifting of scales between enemy echelons. Senior intelligence officers use their access to senior leaders and battlefield proximity to frame their conceptual understanding of the four questions and submit narrative drafts to their intelligence cell to fill in the details. In this way, senior intelligence officers lead their intelligence cells, ensuring unity of effort and complete narratives.

When visualizing the enemy, use these techniques to strengthen your narratives. It may improve decision making in your unit, as it did for the 1st Infantry Division. It may even allow the senior intelligence officer to get some rest!

Endnotes

I gratefully acknowledge the many people with whom I work and throughout my time attending professional military education who influenced the content of this article. I want to recognize Major General Monté ́Rone for his ideas on leveraging commander’s language when briefing and Major General John Meyer for his thoughts on conveying information to busy senior executives. I also want to thank retired Brigadier General Mark Odom for his mentorship across multiple exercises (command post exercises, a Warfighter, and a division-in-the-dirt rotation at the National Training Center). BG Odom’s feedback significantly improved the G-2 section’s performance, including mine. He positively influenced my thinking on the senior intelligence officer’s role in personally briefing the commander on the narrative during large-scale combat operations. Finally, this article continues to build upon ideas I previously developed, and I am thankful to have previously appeared in the Military Intelligence Professional Bulletin. I cite my earlier works throughout this article. All errors are my own.1. Matthew Fontaine, “A Mission Command Meditation: Intelligence Intent and Guidance,” Military Intelligence Professional Bulletin 50, no.1 (2024): 2–7, https://mipb.ikn.army.mil/issues/jan-jun-2024. In this article, the author discusses the unique role of the senior intelligence officer in greater depth, focusing on the challenges of large-scale combat operations.

2. Matthew Fontaine, “A Mission Command Meditation: Building Intelligence Intuition,” Military Intelligence Professional Bulletin 50, no. 1 (2024): 8–19, https://mipb.ikn.army.mil/issues/jan-jun-2024. For an excellent discussion of the power of dialogue, see William Issacs, Dialogue: The Art of Thinking Together (Crown Currency, 1999).

3. Karl E. Weick, Kathleen M. Sutcliffe, and David Obstfeld, “Organizing and the Process of Sensemaking,” Organization Science 16, no. 4 (2005): 409–421, https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1050.0133. The authors discuss the role of retrospection in sensemaking. Also, for a deeper discussion of how the author’s sensemaking model applies to military operations, see Fontaine, “Meditation: Building Intelligence Intuition,”11–15.

4. Matthew Fontaine, “Get Your Red Pen Ready,” Military Intelligence Professional Bulletin 50, no. 2 (2024): 40–53, https://mipb.ikn.army.mil/issues/jul-dec-2024. The author discusses the dynamism of action, reaction, and counteraction in greater depth.

5. Fontaine, “Meditation: Intelligence Intent and Guidance” and “Meditation: Building Intelligence Intuition.”

6. I acknowledge MG Monté ́Rone for offering “commander’s language” as a narrative guideline.

7. I acknowledge MG John Meyer for his dictum on the need to always present information the same way for busy senior leaders, thereby better enabling their ability to digest information quickly.

8. John Lewis Gaddis, The Landscape of History: How Historians Map the Past (Oxford University Press, 2002), 22 (emphasis mine). I gained an appreciation for Gaddis’s concepts of selectivity, simultaneity, and the shifting of scale as a student in the School for Advanced Military Studies Program.

9. Fontaine, “Meditation: Building Intelligence Intuition,” 10.

10. Charles Burdett, “How to Make Your Story Coherent With the ‘Golden Thread’,” Pip Decks, accessed May 7, 2025, https://guides.pipdecks.com/storyteller-tactics/how-to-make-your-story-coherent-with-the-golden-thread/.

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. Matthew Fontaine, “Stating the Obvious: The Three Keys to Better Intelligence Assessments,” Military Intelligence Professional Bulletin 48, no.3 (2022): 44–51, https://mipb.ikn.army.mil/issues/jul-dec-2022.

14. Here is MG John Meyer’s influence once more.

15. I acknowledge MG Monté Rone for describing “commander’s language” and imploring the staff (and often subordinate commanders) to speak in these terms. See also, Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Publication 3-0, Joint Campaigns and Operations (Joint Staff, 2022), IV-17. For a discussion on the primacy of transitions as it relates to the commander. See also, Fontaine, “Meditation: Building Intelligence Intuition,” 9–10.

16. Fontaine, “Get Your Red Pen Ready,” 42–48. The author discusses operational enemy courses of action and transition enemy courses of action, like failure options, in greater depth.

17. Carl von Clausewitz, On War, ed. and trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton University Press, 1976), 102. Clausewitz makes this point with his concept of friction.

18. Merriam-Webster Dictionary, “dilemma,” accessed May 7, 2025, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/dilemma.

19. Clausewitz, On War, 119–123. Clausewitz discusses how everything in war “looks simple” on the surface, but once experienced, the “difficulties accumulate” to produce an “inconceivable friction.”

20. Alan Watt, “Dilemma: The Source of Your Story,” Janice Hardy’s Fiction University (blog), December 31, 2013, http://blog.janicehardy.com/2013/12/guest-author-al-watt-dilemma-source-of.html.

21. Weick, Sutcliffe, and Obstfeld, “Process of Sensemaking.” This is sensemaking in action. The process I describe is no different from the Army design methodology, specifically in developing an operational approach. For more information, see Department of the Army, Army Techniques Publication 5-0.1, Army Design Methodology (Government Publishing Office, 2015), 5-1—5-7. Incorporating Change 1 dated September 18, 2025.

22. “Plot Twist,” Literary Devices: Definition and Examples of Literary Terms, accessed May 7, 2025, https://literarydevices.net/plot-twist/.

23. Fontaine, “Stating the Obvious,” 47–48. This article discusses the value of estimative language.

LTC Matthew Fontaine is the senior intelligence observer coach/trainer for the Joint Readiness Training Center, Operations Group, Fort Polk, LA. He previously served as the G-2 for the 1st Infantry Division, Fort Riley, KS. His deployments include two tours to Iraq and two to Afghanistan, during which he served as an executive officer, platoon leader, battalion S-2, military intelligence company commander, and analysis and control element chief. He holds two master’s degrees in military art and science, one in general studies and the other in operational art and science, from the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College.