Reclaiming Strategic Imagination: Enhancing U.S. Military Planning and Execution

Jimmy Carter and United States officials meet with the Shah of Iran and Iranian officials.Taken on December 31, 1977, brightened for visual clarity. (Photo courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, colors adjusted by MIPB staff)

Introduction

In recent years, the U.S. military has faced considerable challenges in maintaining effective and insightful strategic analysis at the operational and tactical levels. This stagnation is often attributed to H.R. McMaster’s “strategic narcissism” concept, which describes the tendency to view all potential adversary actions or end states primarily from the perspective of their effects on the United States or Western goals.1 The problem is exacerbated by a lack of deep strategic understanding of the adversary’s capabilities and goals at operational and tactical levels, leading to overly simplistic analyses focused narrowly on when and where the enemy “will attack” without a broader contextual analysis of the adversary’s overall strategic goals, history, and priorities.

The focus on immediate capabilities and probabilities, to the exclusion of detailed evaluation of historical context and actual end states, leads to the repetition of assessments like “the enemy will attack in the next 12 to 48 hours,” which assume a considerable number of strategic goals in the ultimately tactical and capabilities-based conclusion of why, or even if, the enemy will attack. These bottom-line assessments are often wrong, and even when accurate, they do little to inform higher-level strategy beyond the immediate tactical area of operations. This leads to a top-down “Simon says” analytical framework in the way intelligence assessments are briefed.

This article proposes that revitalizing strategic imagination requires rededication to a nuanced understanding of adversaries’ end states, historical contexts, adaptive planning, and the capacity to anticipate and adapt to unpredictability in warfare. Conducting capabilities-based assessments without a deep understanding of context, end states, and imagination is not analysis but merely reporting.

The Role of Historical Context in Strategic Analysis

Historical context plays a critical role in strategic analysis but frequently gets short treatment compared to capabilities-based bottom-line upfront assessments in a tactical setting. Wars and conflicts often arise from deep-seated geopolitical, cultural, and ideological tensions; ignoring these historical dynamics can obscure essential insights into adversarial behavior.

To illustrate this point, Iran’s ambitions are shaped by a unique historical trajectory, including its traditional rivalries, colonial experiences, and the Islamic Revolution of 1979. The 1953 Central Intelligence Agency-led coup that overthrew Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh left a legacy of distrust of Western powers and further solidified Iran’s anti-Western stance, as well as its desire to project power in the Middle East—not by modeling foreign relations on international norms, but by possession of the means and methods to exclude foreign influence. These events point to a deep, long-standing mistrust of what are often pitched by Western powers as neutral or status quo solutions based on international conventions and diplomacy. While a fair interpretation may be that Iran distrusts Western powers, an equally fair reading might be that Iran has a cultural mistrust of any security arrangement based on agreements since, historically, such arrangements have failed miserably to protect its interests. Understanding this historical context allows analysts to better grasp the motivations behind Iran’s actions and craft more nuanced and compelling responses rather than assuming that Iran is simply hostile to every United States force in the area as its de jure enemy.

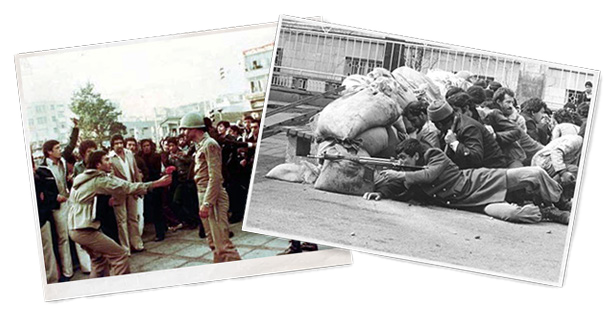

Left: A protester giving flowers to an army officer during the Iranian revolution. Right: Iranian armed rebels during the Iranian revolution. (Public domain photos from Wikipedia)

Unmasking the Adversary’s Desired End State

A fundamental aspect of effective strategic planning is accurately identifying an adversary’s end state. U.S. military analysts at the operational and tactical levels often view adversarial goals through a Western-centric lens, leading to a simplistic and flawed understanding of their motivations. Additionally, Western military strategy focuses on capabilities and effects, leading analysts to believe that our bigger guns will always win the fight. This reductive analysis results in low-value assessments, which add little to raw analysis. Where, how many, and what kind of equipment the adversary possesses is certainly important information, but it is simply regurgitated data. Proper analysis requires understanding how all this data plays into the adversary’s end state. The current conflict with Iran demonstrates flawed binary reasoning: Iran opposes the United States; therefore, every end state necessarily involves attacks on United States troops. While it is true that Iran often directs its network of militias to attack American troops, it is equally valid that Iran’s goals are more complex than merely opposing America—and some of their most important goals are achieved without attacks at all.

Analysts have consistently underestimated Iran’s ambitions to establish itself as a dominant regional power, driven by a complex interplay of religious ideology, historical grievances, and nationalistic pride. Iran’s end state involves more than mere survival or military dominance; it seeks to fundamentally reshape the Middle East according to its vision of an Islamic Republic that challenges Western influence. Iran’s support for proxy groups across the region is part of a broader strategy to influence regional politics and shift the balance of power in its favor, irrespective of that end state’s ultimate effect upon the United States. Analysts who fail to grasp this underlying motivation may misinterpret Iran’s actions as reactionary or opportunistic rather than as part of a long-term strategy for regional dominance. For example, Iran’s support for groups like Hezbollah and the Houthis is not only about immediate military objectives but also about building a network of influence that extends Iran’s reach and destabilizes rival powers, regardless of individual tactical engagements by the proxies and equally unrelated to whom those proxies target.

If we view the proxies as Iran’s public projection of force, in the same way that a United States carrier group is a representation of American power, their mere existence and presence are as helpful as their actual utilization because the goal is to demonstrate regional influence more than to achieve specific tactical objectives. Understanding this intent is crucial for accurate assessments and effective counterstrategies. This is especially true when Iran’s interests align with those of other regional actors—for example, Hamas—with little or no interest in United States troops.

While Iran and Hamas may align against common adversaries, conflating their ultimate strategic goals can lead to significant miscalculations because one involves direct conflict with United States troops, and one does not. Iran’s goals focus on establishing itself as a dominant regional power with substantial influence over the Middle East. In contrast, Hamas is a militant Palestinian organization focused on issues related to Palestinian self-determination and resistance against Israeli occupation. Hamas’s goals revolve around achieving Palestinian statehood and resisting Israeli control over Palestinian territories. While Hamas and Iran occasionally cooperate, their objectives are fundamentally different. Hamas’s focus is on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and Palestinian sovereignty, while Iran’s ambitions are broader, aiming to reshape the balance of power in the Middle East.

Understanding this distinction is crucial for U.S. military analysts. Misinterpreting the alignment between Iran and Hamas as indicative of a unified strategy can lead to flawed analysis. For instance, Israeli actions targeting Hamas might not necessarily affect Iran’s broader regional ambitions and could even strengthen Iran’s position if it appears as a defender of Palestinian causes. Accurate differentiation between countering Iran’s regional hegemony and addressing the Israeli-Palestinian conflict requires that analysts have a deeper understanding of the regional actors’ goals, which, in turn, requires a renewed and deeper focus on history and context instead of capabilities and reassessing the assumption that every adversary of the United States is working in concert. Arming our tactical and operational analysts with a deeper understanding of the adversary’s objectives and strategic aspirations allows them to craft more astute analyses.

Backward Planning: A Useful Tool for Analysts

As determined through historical context, the end state provides the raw material for one of a planner’s most important tools: backward planning. Backward planning is a strategic process that begins with an adversary’s end state and works backward to identify potential actions and interventions. For Iran, this involves first understanding its goal of regional dominance and influence, which includes supporting proxy groups, leveraging economic sanctions as propaganda, and manipulating regional conflicts. Without this historical context, backward planning is starved of the antecedent facts necessary to make the assumptions required to use the process effectively. In other words, backward planning enables military planners to anticipate Iran’s moves by considering how the country might use its resources and influence to achieve its strategic objectives based on its end-state goals, which are, in turn, based on historical context. For example, if Iran aims to project power through proxy groups, planners can anticipate where these proxies might be active and develop countermeasures accordingly. By adopting this approach, planners can improve their strategic foresight and prepare more effectively for potential scenarios beyond merely reacting to specific tactical objectives by any single proxy.

Understanding Flukes

Finally, the analyst or planner must acknowledge the predictably unpredictable nature of the strategic environment. In his 2024 book Fluke: Chance, Chaos, and Why Everything We Do Matters,2 Brian Klaas includes one striking example of how small, seemingly random events can shape history. During World War II, United States Secretary of War Henry Stimson was deeply involved in discussions surrounding the use of atomic bombs in Japan. Stimson had a personal connection to Japan: he and his wife had visited Kyoto during a pre-war trip and developed a fondness for the city’s cultural and historical significance. This personal experience led Stimson to advocate strongly for sparing Kyoto from the bombing list, citing his affection for the city and the memories of his visit with his wife. As a result, Kyoto was removed from the list of potential targets for the bomb, and Hiroshima became one of the final cities selected.

Klaas uses this anecdote to illustrate how chance and personal experience can dramatically shape decisions that have profound global consequences. In this case, one man’s attachment to a place helped determine the course of history, demonstrating how individual human choices, shaped by unpredictable life events, can have monumental impacts in war’s chaotic and complex context. This example underscores the need for flexibility in planning at all levels, as fluke events can dramatically alter the strategic landscape. Planners must be prepared to adapt to sudden changes and reassess strategies in light of new developments. To do this, planners must concern themselves with history, culture, and societal influences as much as capabilities and probabilities. Knowledge of the personalities and histories of the leaders and significant actors is also a critical element in effective analysis, but one which is often simply not included in typical tactical briefings.

Summary

Reclaiming strategic imagination among tactical and operational analysts requires a nuanced understanding of adversaries’ historical contexts, end-state goals, and the ability to anticipate and adapt to unpredictable events. By integrating these elements into military operations and incorporating backward planning from the adversary’s perspective, U.S. military leaders can make more informed, flexible, and creative decisions. This approach not only enhances the effectiveness of military strategy but also ensures that the United States remains adaptable in the face of evolving threats and dynamic geopolitical environments. For the intelligence community, this means fostering a culture of strategic imagination that embraces complexity and unpredictability, ultimately leading to more robust and resilient defense strategies.

Endnotes

1. H.R. McMaster, Battlegrounds: The Fight to Defend the Free World (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 2020).

2. Brian Klaas, Fluke: Chance, Chaos, and Why Everything We Do Matters (New York: Scribner, 2024).

CPT Nader Badran is the officer in charge for the Joint Security Area Analysis Branch, U.S. Army Europe and Africa Theater Analysis and Control Element, 24th Military Intelligence Battalion, 66th Military Intelligence Brigade-Theater. He previously served as the brigade S-2, 401st Army Field Support Brigade at Camp Arifjan, Kuwait.